World War 2 “Points” the Adjusted Service Rating Score or ASRS, the system for calculating the eligibility of when a U.S. Soldier was allowed to

In early as mid-1943, as troops were being shipped all over the world, it was becoming obvious that bringing all the Soldiers, Sailors and Marins back home after the war was going to be a huge logistic challenge. The U.S. military about 12 million strong in 1945, with approximately 3 million Service men an women in Europe.

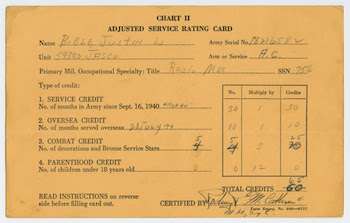

On May 10, 1945, two days after Germany’s surrender, the War Department announced a point system to decide who gets to go home first. In this system, every service member received 1 point for every month in service and an additional 1 point for every months of service spent overseas. Awards, namely the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Soldier’s Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, the Air Medal and the Purple Heart, were worth 5 points each. The Combat Infantryman Badge was not worth anything, leading to much grumbling among the troops.

Campaign participation credits were also worth 5 points each. American participation in the war was divided into 16 separate campaigns, but even the most battle-hardened units only participated in up to nine of these. Finally, each dependent child under 18 years of age was worth an additional 12 points. Moreover, men with three or more minor children could go home regardless of their score. It should be noted that age, marital status and dependents above 18 were not factored into calculating the score.

Initially, service members needed 85 points to go home. Once this was reached, further points did not count towards even higher priority: someone with, say, 105 points was not guaranteed to go home before one with only 85. Another cause for complaint was that the system didn’t reflect the nature of service: a month spent in the rear was worth just as much as a month on the front lines. Initially, officers were not subject the point system: they would go home or continue to serve based on their efficiency and special qualifications.

Units in Europe were placed in four categories. Category I units, consisting of men with low scores were designated as occupational forces and would stay quite a while. Category II units still had a ways to go and were either to redeploy to the Pacific, directly or via the U.S., or return to the States and stay in strategic reserve. Category III units were to be reorganized and then placed in Category I or II. Finally, Category IV units were those with 85 or more points, waiting to be sent home and demobilized.

One practical problem with the system was the categories were designed for units, while the score applied to individual soldiers. As a result, soldiers had to be shuffled around en masse to place all high-scoring soldiers in Category IV units and low-scoring ones to others.

Once demobilization started in earnest, it actually progressed quicker than anticipated thanks to the efforts of Operation Magic Carpet. As a result, the score needed to go home was revised and lowered several times, with different limits established for different types of personnel. In May 1945, for example, limits just within the Medical Corps varied from 88 for administrative personnel to 62 for hygienists and dietitians.

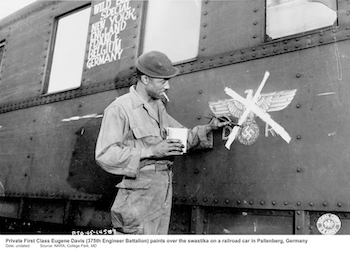

By September 1945, demobilization was proceeding at such a pace that units still in Europe were re-designated according to a new system: Occupation Forces who would stay, Redeployment Forces who would go home and Liquidation Forces, whose soldiers had credits of about 60-79 and had the job of closing down former frontline facilities such as ammunition dumps and field hospitals before getting demobilized.

In December, 1945, an overhaul of the system incorporated the length of service. An officer, for example, could go home with 70 points, but only if he had served for at least four years. In contrast, enlisted women could go home with as little as 32 points and no minimum service time.

By early 1946, the rapid pace of demobilization was causing a manpower shortage in occupation troops in Europe and Japan. Consequently, the War Department slowed the process down. This sparked a slate of protests worldwide. On January 6, 1946, 20,000 soldiers marched on their headquarters in Manila in the Philippines after a ship home was canceled at Christmas. Protests with tens of thousands of participants started in Germany, Austria, France, the United States, India and various Asian locations. A few service members were arrested but Eisenhower suggested they should not be penalized. Demobilization was sped up again and measures were introduced to make overseas service more palatable: training was made shorter, soldiers’ families were able to move to his place of service free of charge and European occupation troops were offered 17-day tours of Europe for a nominal price.

Take a look at these other WW2 Posts:

- The U.S. Army Parachute Test Platoon

- The Other D-Days