He was 17 when he enlisted as a private, lying about his age as he knew his adoptive parents wouldn’t give their consent. He was posted in Panama, where a sergeant took him under his wings and made him his assistant. Gavin’s basic education was sorely lacking as he had to work as a child to help support his family but his mentor persuaded him to join a local army school. He graduated as one of the best, which earned him the chance to attend West Point, where he studied hard. His lack of education was a great disadvantage and every day he got up before dawn to take his school books to the bathroom, the only place with enough light to read.

James Gavin

After graduating from West Point, he was posted at the Mexican border for three years, then attended the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning. The school’s manager, then-Colonel George C. Marshall, and Joseph Stilwell, head of the Tactics department, taught him lessons that went against accepted American military thinking of the time. He adopted their philosophy of avoiding micromanaging subordinates and giving them rough guidelines and the freedom to make tactical decisions on their own.

Gavin also became fascinated by the writings of British officer J.F.C. Fuller, one of the early theoreticians of armored warfare. A 1936 posting to the Philippines also made him wary of Japanese military might and aware of how the U.S. was falling behind other countries in weapons development.

When World War II broke out, Gavin returned to West Point as a highly popular instructor and researcher into German tactics and equipment. He became a proponent of airborne forces and wrote the U.S. Army’s field manual on airborne tactics: Tactics and Technique of Air-Borne Troops.

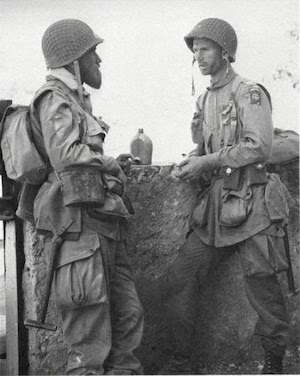

He helped transform the 82nd Infantry Division into the 82nd Airborne, and became commander of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, leading training marches in person, and telling his officers to always be “the first out of the airplane door and last in the chow line”, a tradition preserved by the airborne to this day. Gavin’s hands-on leadership style made him the only American general in the war to make four parachute jumps with his troops.

During the Allied invasion of Sicily, the 505th PIR became the first ever American unit to perform a regiment-sized airborne landing. Strong winds scattered the group and Gavin landed far away from his zone, spraining his ankle during landing. His small group started making their way back towards their objective in the dark, harassing the much larger Axis forces with guerilla tactics. After one particular skirmish, he had to leave the wounded behind, going on with his last six men. “This is a hell of a place for a regimental commander to be” – he exclaimed.

Gathering scattered paratroopers, infantrymen and later clerks, cooks and truck drivers, he captured and held the vital Biazza Ridge against an overwhelming German force which threatened to attack the exposed flanks of two divisions. Turning two pack howitzers into direct-fire weapons, the group managed to knock out a Tiger and hold the ridge until relief arrived.

General James Gavin jumped again with his troops the night before D-Day, this time into Normandy. The jumps were scattered over a wide area and he was willing to put himself at risk in the chaotic fighting of the first couple of days. During the final push for the La Fière causeway, both he and his superior, General Matthew Ridgway, participated in a charge down an exposed path into heavy enemy resistance, stopping in the killing zone to remove an obstacle.

He jumped once more during Operation Market Garden, suffering another injury on landing. A few days later a doctor told him he was fine but a more thorough check-up five years later revealed he fractured two spinal disks. Not much later, the 82nd was deployed to the Ardennes to defend against Hitler’s last major counterattack in the West. The division fought in the northern sector of the battle, facing Kampfgruppe Peiper , the German unit which earned infamy with its massacres committed against captured U.S. soldiers and local civilians.

After the war, James Gavin became one of the early actors in the racial integration of the U.S. military, when he oversaw the incorporation of the all-black 555th PIR into the 82nd Airborne. He assisted his fellow airborne general, Maxwell Taylor, in the creation of Cold War-era Pentomic Divisions. As Army Chief of Research and Development he called for the use of airborne mechanized infantry as a sort of modern cavalry, his intention eventually culminating in the heavy use of helicopter-borne troops during the Vietnam War.