A Pencil and a Rifle

A Pencil and a Rifle

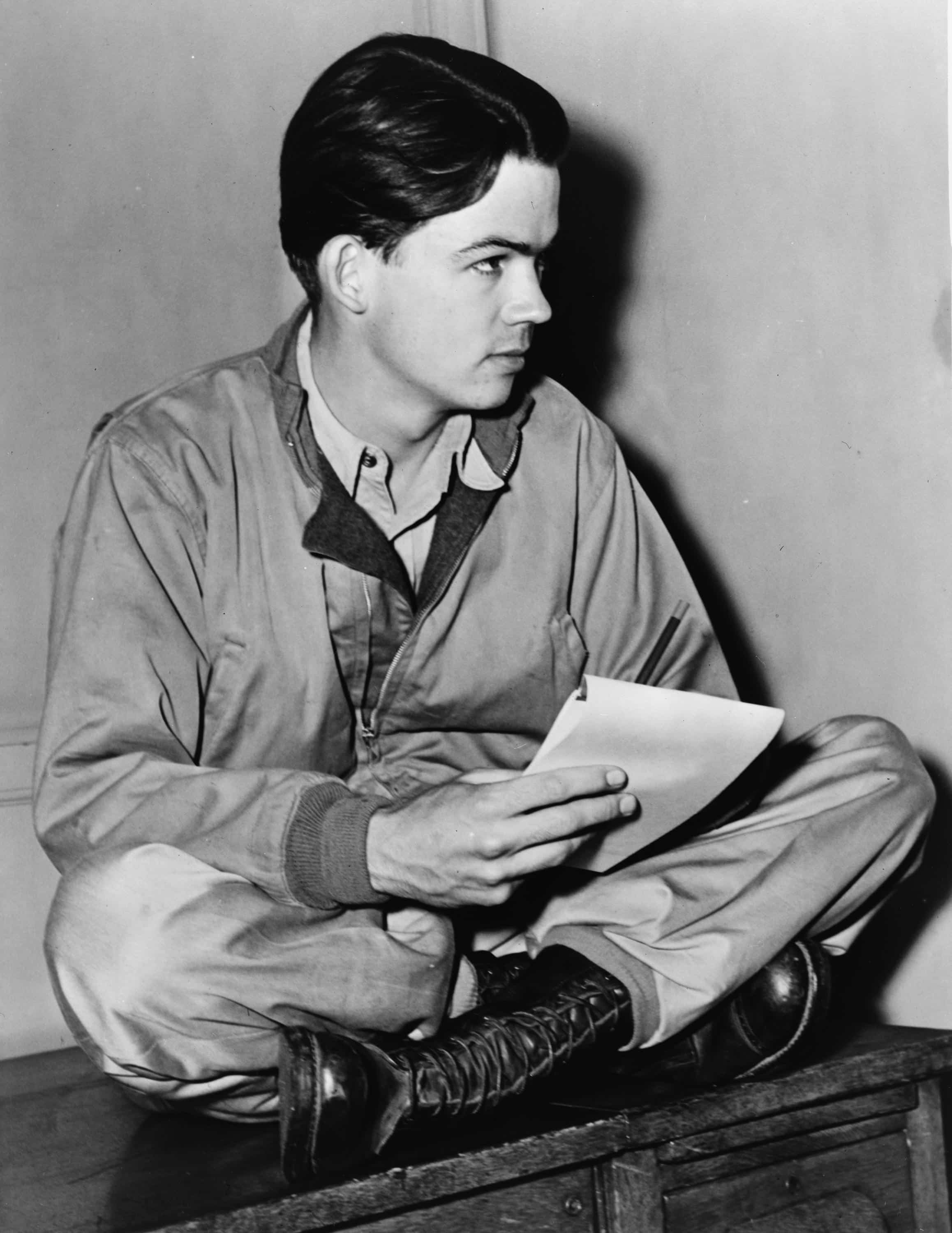

He wasn’t a general or a war correspondent with press credentials. Bill Mauldin was a rifleman — one of millions of dogfaces who trudged through Europe’s mud, slept in foxholes, and learned to laugh at misery because the only other option was to cry.

Born William Henry Mauldin in Mountain Park, New Mexico, in 1921, he came from a line of men who understood hard ground. His father was a World War I artilleryman. His grandfather had been a frontier scout. By his late teens, Bill’s world was the Great Depression — dust, hunger, and the occasional spark of opportunity.

When he found art, it wasn’t in Paris or Chicago. It was in the quiet lines of a correspondence course, drawn by flashlight in a small desert town. He learned fast, studied cartooning at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts under Pulitzer-winner Vaughn Shoemaker, and by 1940, he’d joined the Arizona National Guard. He was nineteen, thin, and restless — a kid who packed a rifle and a sketchbook.

The 45th Infantry and the Making of a Voice

The 45th Infantry Division — the “Thunderbirds” — was a rough collection of citizen-soldiers from the American Southwest: ranch hands, miners, mechanics, and farm boys. When the division was federalized, they trained hard, cursed often, and waited for the call.

During field exercises at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Mauldin started sketching what he saw: soldiers wrestling with equipment, groaning under packs, and trying to find humor in the Army’s endless rules. His cartoons appeared in the division’s paper, The 45th Division News.

At first, the brass liked him. His sketches lifted morale. But his humor had teeth — and he aimed it upward. Officers became caricatures. Orders became punchlines. The more realistic he drew the dogfaces, the more the dogfaces loved him.

From Sicily to Italy: Drawing the Front

When the 45th hit the beaches of Sicily in 1943, Mauldin was there, rifle slung over one shoulder and sketch pad in his pack. He saw men dig into volcanic soil under artillery fire, slog through vineyards, and scrape mud from boots that never seemed to dry.

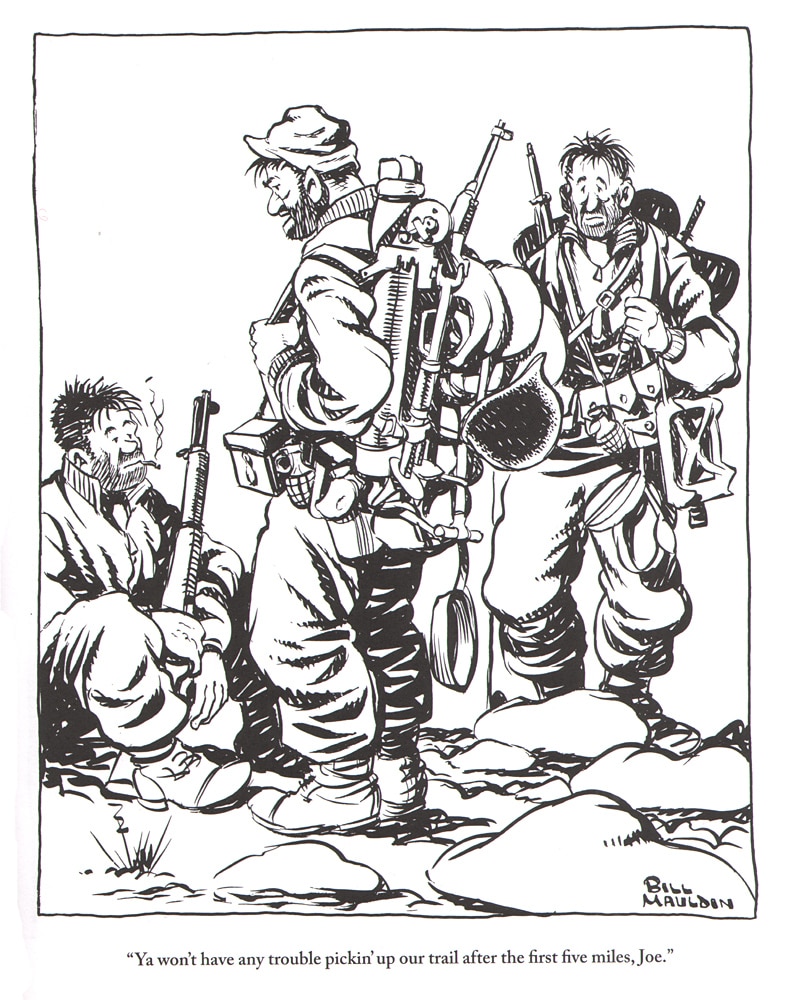

From those days came Willie and Joe. They weren’t heroes — not in the movie sense. They were tired, unshaven, hollow-eyed infantrymen who embodied every man in a dirty uniform. Mauldin gave them a voice that sounded like the front lines: weary, wise, and sarcastic.

One cartoon showed Willie telling Joe, “I feel like a fugitive from the law of averages.” Another had them trudging through the rain, muttering about “them fresh, spirited American troops” the papers kept talking about. The soldiers laughed because it was true. Civilians winced because it wasn’t the image of victory they’d been sold.

Stars and Stripes and a War in Ink

Stars and Stripes and a War in Ink

By 1944, Mauldin’s sketches had caught the attention of Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper that reached across every front. He was reassigned to their staff, armed with a jeep, a press pass, and permission to go wherever the fighting was worst.

He followed the troops through Anzio, Cassino, and Rome, drawing in foxholes and bombed-out farmhouses. His cartoons appeared almost daily — little rectangles of truth printed in ink and sweat.

Not everyone was amused. General George S. Patton, immaculate and iron-willed, loathed Mauldin’s “scruffy GIs” and threatened to shut him down. Patton called him “unpatriotic.” Mauldin met him once — the general in pressed uniform, the cartoonist in muddy fatigues. When Patton lectured him about discipline, Mauldin nodded politely and went right back to drawing.

General Eisenhower, on the other hand, told Patton to leave him alone. “If it makes the men laugh,” Ike said, “let them laugh.”

The Soldier’s Conscience

The Soldier’s Conscience

Mauldin wasn’t just drawing gags — he was recording history. Each panel captured what every combat veteran knew but couldn’t always say: the absurdity of war, the distance between front-line reality and command fantasy, the way humor kept men sane when the world went insane.

In March 1945, Stars and Stripes published one of his most enduring images: Willie and Joe standing at the door of a bombed-out building, watching clean, fresh replacements march by. “Beautiful view, ain’t it?” one says. “Yeah — pity it’s ours.”

For those who’d been there since Sicily, it said everything.

That year, Mauldin received the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning — at age 23. He accepted it not as a celebrity but as a spokesman for every nameless dogface who’d done his time in the mud.

Back Home and at Odds

The war ended, but Mauldin didn’t celebrate. He came home to a world that didn’t quite understand the one he’d left. His 1947 memoir Back Home told that story — of a veteran trying to find his place among people eager to forget.

He drew political cartoons, ran unsuccessfully for Congress, and refused to become a propagandist. His pen stayed honest — sometimes to his own detriment. He spoke up for veterans, for free speech, for civil rights. When others wanted quiet patriotism, he gave them truth.

The world had changed, but so had he. The mud never quite left his boots.

The Second Pulitzer and the Next Wars

In 1959, now working for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Mauldin earned a second Pulitzer Prize for a cartoon depicting Soviet writer Boris Pasternak behind bars saying, “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?”

It was vintage Mauldin — empathy for the underdog, defiance toward power, drawn in clean, telling lines.

By 1962 he’d joined the Chicago Sun-Times, where his cartoons tackled civil rights, Vietnam, and the moral weariness of the modern age. He never stopped giving voice to the ordinary man caught in the gears of history.

After President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, Mauldin drew one of the most powerful images of the century: Abraham Lincoln’s statue at the Lincoln Memorial, head bowed, hands covering his face. No caption needed.

Willie, Joe, and the Memory of Mud

In later years, Mauldin returned now and then to his wartime duo. Willie and Joe aged along with their creator — tired, gray-haired, haunted by the same ghosts that lived in so many veterans’ memories.

Other cartoonists, like Charles Schulz of Peanuts, honored him. On Veterans Day 1998, Schulz drew Snoopy shaking hands with Mauldin’s Willie and Joe — a quiet salute from one generation of artists to another.

Mauldin’s last years were spent battling Alzheimer’s, but his drawings remained etched in the minds of those who’d read them in muddy tents or field hospitals decades before. He died on January 22, 2003, at age 81, and was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery among the men he had immortalized.

Legacy of a Muddy Pencil

Bill Mauldin didn’t just draw cartoons — he drew a bridge between the soldier and the world that sent him to fight.

His art stripped away the slogans and the glory, revealing something truer: courage wrapped in fatigue, humor born of hardship, and dignity found in dirt.

In the end, Mauldin gave us something no war correspondent could — the soldier’s own reflection, sketched by one of their own. Through Willie and Joe, he made sure the infantryman’s story would never be forgotten.

Stars and Stripes and a War in Ink

Stars and Stripes and a War in Ink The Soldier’s Conscience

The Soldier’s Conscience